OK Go – Red Star Macalline Commercial

Production Diary by Camera Operator, Alec Jarnagin, SOC

Originally Published 4/18/2015

Photographs by Jendra Jarnagin

Illustrations by Director of Photography Luke Geissbuhler

I keep getting lots of inquiries from people interested in the details of how we achieved this unique and impressive video, so I thought it best to share my experiences in a blog article.

First off, if you have not seen the video, or you want to watch it again:

This article will make much more sense if you watch these two “Behind the Scenes” video before reading.

FIRST CONTACT

While I was attending the Sundance Film Festival in late January, I got a very interesting phone call from my friend, Director of Photography Luke Geissbuhler. He was calling from Shanghai, China where he was scouting a commercial featuring the American band OK Go for the Chinese furniture company Red Star Macalline (think IKEA of China). With OK Go’s reputation for amazing, mind-bending and challenging videos, my interest was piqued immediately. The video was to be co-directed by OK Go lead singer, Damian Kulash and their long time collaborator and Creative Director, Mary Fagot. Luke set about describing that they were revisiting the song “I Won’t Let You Down” (remixed by the band’s drummer, Dan Konopka) complete with optical illusions, in-camera zooms, and people walking on walls! The optical illusions would require the camera to land within one-inch accuracy in all dimensions. I asked if the camera was “finding” these positions visually, or landing on them suddenly to reveal the illusions to which he told me that most of them would involve an instantaneous reveal, with the key elements “popping” into view. Because of the required precision and repeatability, I asked whether it would be prudent to shoot it with a “Motion Control” rig, instead of Steadicam. Luke replied that the space was too vast and due to the nature of the video, it would not be feasible to be limited to the tracks that Motion Control requires. We then discussed a number of other possible ways to shoot it, but it kept coming back to Steadicam, which both excited and terrified me because of the precision required.

ENVISIONING THE IMPOSSIBLE

Over the weeks to come, many emails and phone calls were exchanged trying to figure out the specifics of how to do this. To achieve the “walking on walls” segment, they were building a spinning hallway (aka “The Wheelhouse”) where two members of the band (Damian and Tim) would have to navigate moving furniture and light fixtures as the walls around them spun. The camera would somehow have to spin at the same speed as the room so it would appear as if our heroes were defying gravity and doing a magical dance. To achieve the camera rotation, they wanted to somehow dock/affix the Steadicam to a crane and have the camera spin in sync with the hallway. Luke and I considered many options of how to do this, none of which were practical for various reasons.

Then the MK-V “MR” (for “Manual Revolution”) occurred to me. This is a simple carbon fiber roll cage for a camera intended to mount on top of a Steadicam sled, allowing the operator to manually spin the camera upside down for low mode. I wondered if one could be controlled by a Preston motor…. I then put out an inquiry on Steadicamforum.com looking for one. Fellow Camera Operator, Ramon Engle, responded he had something that might work for me. He had modified his “AR” rig (“Auto Revolution”/ “Alien Revolution”) to use the existing internal motor to spin the camera via a Preston Microforce to control it. All the auto-leveling sensors and abilities were removed. In short, it was exactly what I was looking for!

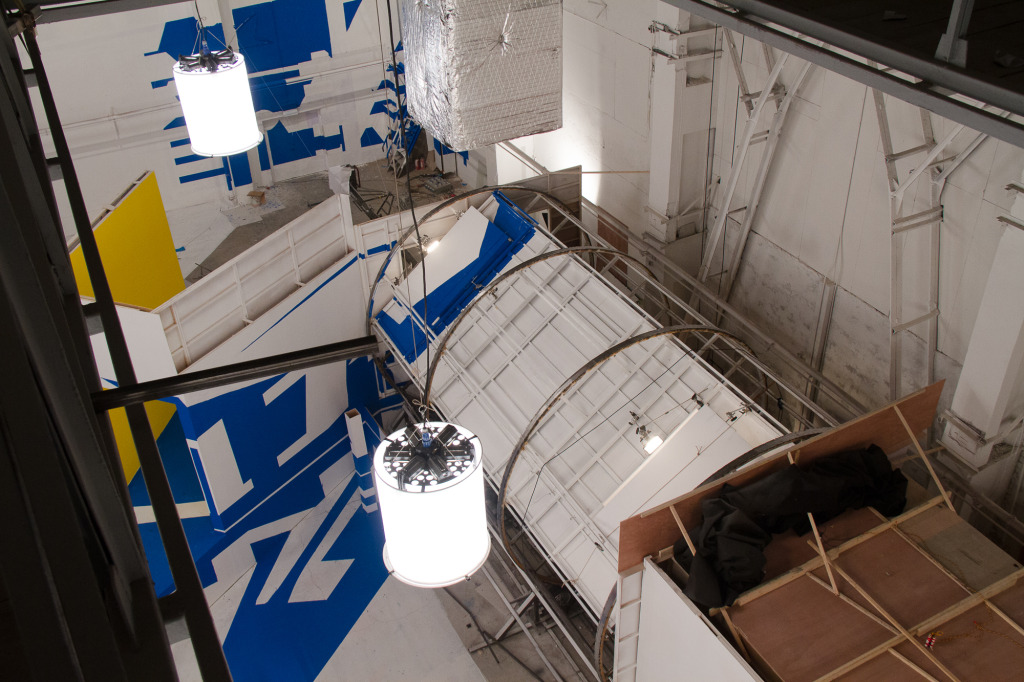

“The Wheelhouse” in Action, as seen from above

NEXT UP – THE ZOOM & OTHER FACTORS

Yes, right after the spinning hallway, they wanted to do a “crush zoom” (aka “squeeze shot”or “Vertigo shot”). We’d be zooming from approximately 18mm to 100mm. Then as the camera pushes in and we zoom out, an optical illusion would be revealed. For this we chose the Canon 17-120 lens since it was lightweight and covered the full 6K we were shooting on a RED Dragon.

Of all the marks required to reveal the optical illusions, I was most concerned with height. I’ve long been a fan of taped “V” marks on the ground and was fairly certain that they’d get me where I needed to go in terms of hitting a mark on the floor (we’d add a laser pointer to help with this). Having the arm boomed to an exact height is not something I’ve ever given too much thought to however. Sure, you can judge the relationship between your boom hand and vest spar as a rough guide, but I feared this would not suffice. So, we planned on using a Cinetape mounted to the bottom of the sled so the “guns” would be pointed to the ground and the display would be mounted on my monitor arm rods so I could see our height easily.

“V” Marks help me back into precise positions.

CHINA!

I love to travel and indeed that is part of the reason I got into the film business. While I had been to Beijing before, this would be my first time in Shanghai. We were scheduled to have three “build/test/rehearsal” days and two “shoot” days. I requested to fly over a couple of days beforehand to acclimate and see a bit of the city (my wife, Jendra, was to join me late in the trip). Upon arrival, I discovered that the Cinetape we had asked for was substituted for the Arri version. This would have been fine except we didn’t have the correct power cables (I even brought my own for the Cinetape). The rental house had not included a P-Tap power cable for the Arri version. When I explained we needed a P-Tap cable, the rental house responded “this device was only to be used with an Arri camera!” But we were using a RED Camera (provided by them). They had sub-rented the Arri Tape from a company in Beijing and they didn’t want to hear it. When I talked to my 1st AC about modifying the one cable we had, the unit “disappeared” and was sent back to Beijing. (Chinese rental houses send representatives to set that remain with the gear at all times – their own insurance, I guess, and when one of them saw our intentions, they simply sent the gear away.) And there went my idea of using a Cinetape to find lens height!

However, one of the wonderful things about working in China was the huge machine shop/grip rental house on the studio lot owned by our talented Production Designer, Julius Mak. If we needed something mechanical, it could be built in no time! Luke and I took advantage of this during the “test” days by having a number of physical devices built to see if there was a way to aid the Steadicam sled to hit a precise mark. Because there was still a lot of construction happening on the main stage, I’d hang out in a neighboring stage, building optical illusions with random grip gear and Chinese letters to see how accurate I could get, hitting critical marks. The devices we built ranged from flexible plastic rods that could be placed by the front of the Steadicam monitor, to planting the sled on a foam pad, and experimenting with “V” shaped wooden “docks” lined with foam to slide the Steadicam post into. In the end, I found all of these methods distracting and too time consuming to use (the pace of the video was too fast) and I concluded that I was better off using my 20+ years of Steadicam muscle memory. All said and done, I was glad to have exhausted our options and had the chance to show Luke the various methods we had at hand. Plus, I really wanted a bag of tricks at the ready, since I was still pretty nervous about this whole thing. In the end, we did indeed use one of these gadgets to achieve the final illusion.

The crane is extracted from “The Wheelhouse.” Note the camera angle in the roll cage.

THE ROTATING HALLWAY, aka “The Wheelhouse”

For this section of the video, the camera precedes our band members down a hallway and I board a crane that lifts me off the ground (just high enough to clear the furniture that needs to pass under me as the hallway rotates around the crane.) At the same time, the camera is spun in the AR roll cage at the same speed as the room so it looks like the band walks on the walls and ceiling. Good fun. Easy, right? Well, in theory. One thing that makes a crane step-on or off work is making it invisible to the viewer. If you are waiting for the crane to move, it gives it away. In order to hide the first section of the hallway (the part that does not rotate) from the camera, band members Andy and Dan drop a roll-down screen with a picture of themselves. In addition to being a funny trick to hide them and leave them behind (so they can run around the set to re-appear later), it serves as a wonderful stall to get on the crane and “feather” the lift-off before the floor begins to spin. Since all the timing is coordinated with musical cues, in order to finesse this transition, we needed to get down the first part of the hall as quickly as possible, which involved a pretty fast run backwards. This was actually not very difficult as I had a door in the distance by which to align myself, which meant that once it was “in front” of me, I was clear to run backwards without fear of hitting anything. Once the paint of the hallway walls changed color, there was a red sofa to my right and as soon as I cleared this, I was hitting the crane platform. A few people have asked me about the size of the crane platform because you can see how small it is in the Behind-the-Scenes video. I’ll say this: it needed to be this size so that the furniture would clear it on the spin. A small platform means you hit the speedrail “T” backrest as soon as possible (you don’t have time to get “lost” on the crane). I take safety very seriously as does our DP, Luke. Long before I ever set foot in China, I made sure we were well under the maximum load capacity of the crane (a 30 ft GF8 from Grip Factory Munich). If I were traveling higher off the ground, I would have wanted a larger platform, but that said, a fall from this short height onto a moving floor could still have been a disaster. We had a person with a kill button standing at the edge of the platform at all times and frankly with the speedrail “T,” I felt very secure and safe. Hell, once onboard, it was like a desk job!

DP, Luke Geissbuhler, calculated every possible dimension during prep. Not a lot of room for that crane!

Coordinating the spin of the AR and the rotation of the hallway turned out to be one of the most difficult parts of the entire video. So much so that our 1st AC (Kenan Qi, aka “Conan”) opted to control this (as well as the crush zoom) and have his 2nd AC pull focus! The rotating hallway was very bottom-heavy, meaning that the speed of the rotation was not consistent. When the floor was up in the air, it fell (i.e. the second part of the rotation) at a much higher speed than the first. This meant that the Microforce controlling the rotation of the camera could not just be set to a given speed to match. Luke wanted to add weight to the top of the spinning hallway to even out the speed, but the engineers were were afraid that the already swaying structure would break and nobody wanted to be the guy who “broke the wheelhouse” and have us shut down! Because we were shooting 6K, we had an 8% margin of error with the rotation (meaning that if need be, we could smooth out any inconsistencies in post as long as we were never off by more than 8%).

Because we were shooting 6K, we had an 8% margin of error with the rotation of the camera.

THE FINAL ILLUSION

Nothing like saving the hardest thing for last…. The final illusion is the word “Macalline” forming from abstract shapes as I back up a ramp, in order to get the required height. This illusion had ZERO margin of error: a centimeter off and the letters fell apart (especially the “C”). Even though I could slow down my walk, which would be sped up in post-production, (the people in frame were frozen in place,) the letters still needed to “pop” into formation for dramatic impact. No camera searching was allowed. Luke was rightfully adamant that we explore “docking” options for the sled to hit an exact mark. While the concept of anything hitting the sled goes against my years of training, I knew he was right. We built into the set two foam-lined forks that we’d gently slip the Steadicam into. Any bump would just have to be removed in post (which wouldn’t be a big deal since we were changing the speed of this portion anyway). Because I was going up a ramp backwards, we really had to play with the angle of this dock so I could see it (we used a “V” mark on the floor, of course). I should add that I never took the arm out of the gimbal, so it was not docking the sled in the traditional sense.

Hitting the “Hard Mark” for the End

THE SHOOT

Day 1: We broke the video into three parts allowing us to rehearse the move in sections. Part One took us to the hallway. Part Two took us through the hallway and crane move. Part Three was from the crush zoom until the end. By the end of shoot day one, we had rehearsed all three sections and then did some run-throughs of the entire thing handheld on a Canon 7D. The Steadicam sled was parked by the spinning hallway so the AC could practice the spin of the AR. Things were finally looking possible. We ended the day by shooting the 30 second version of the spot, (for broadcast in China) which was a much simpler version.

Day 2: We still had technical things to work out. Some of the optical illusions were being modified, which requires putting a projector where the camera mark is, projecting the “illusion image” on the wall then matching the practical illusion to it (via paint, signs, aligning foreground objects, etc). They were also still painting parts of the set. So, we began by rehearsing the parts of the video that we could. I can’t actually recall when we started to roll but I think it was not until after lunch. Damian, Mary, Luke and I all agreed to roll once we began full run-throughs with the Steadicam, despite the white floors needing massive clean up after each take because of footprints: the crew had to wear booties and I had two pairs of shoes that I’d swap out if I ever left “the clean zone.” Of course, the early takes were a disaster – particularly the timing of the AR spinning in sync with “The Wheelhouse.” There was just no way to predict the way the hallway would behave – in addition to the bottom-heaviness, the timing of the spin was always different. Between takes, they’d work on it.

Spirits were still high though! The band is amazing; overcoming myriad challenges goes with the territory of being such visionary ground-breakers. Damian was a true inspiration. He kept things light, yet focused. These are the type of people that you relish working with. DP, Luke Geissbuhler and I felt like we were in the trenches of a war together! We had come to the same conclusion on our second test day – that Luke should be the one to spot me. There is no dedicated grip department in China so it would have been one of our camera people spotting me and frankly, we couldn’t spare any of them (and I really needed someone who was fluent in English.) It may sound silly, but a spotter on a job like this IS everything. Besides, there was no room for another person in the hallway and Luke wanted to be in there so he could see why something was or was not working, which was impossible to tell from video village. Furthermore, with one of our directors starring in the video, watching playback was already a necessity.

Walking Backward up the Ramp for Grand Finale.

HOW MANY TAKES?

At some point, Damian began to dedicate the takes to people as we slated. We had all agreed if we got a “star” take, we’d immediately go again instead of watching it, to keep us in a groove. At around midnight, we had two or three starred takes but still felt we could do even better and had just enough time for two more takes. Takes 20 & 21 were both named after my wife, Jendra, who was on-set visiting us at this point. What you see in the finished video is Take 21, the final take, in its entirety as one continuous take – no cuts, no secret wipes, no blending of takes – with some speed changes in post as well as a few frames dropped to achieve the “jumps” during the zoom-in, which was always the plan.

CONCLUSION

Being a part of this video – in China no less! – was both a personal and professional highlight for me. For all involved, the challenges were borderline comical and indeed in many ways, it was the hardest shoot I’ve ever done. Pulling it off however, makes it that much more rewarding. If we had merely made an “OK” OK Go video, what would have been the point? This band continues to raise the bar on their productions and if we had taken a step backwards, none of us would have been satisfied (most of all, the viewer!).

L to R: Damian Kulash, Mary Fagot, Tim Nordwind, Luke Geissbuhler, Alec Jarnagin, Dan Konopka, Andy Ross, Lingyi Chen, Julius Mak, Sunny Ong Wan Hoong

For more about Alec Jarngin, SOC please visit: http://www.alecjarnagin.com

EQUIPMENT USED:

RED Dragon (shot at 6K)

Canon 17-120mm lens

Preston Remote Focus

GPI PRO 3HD sled (with XCS post and gimbal)

GPI PRO arm & vest

Modified MK-V AR owned and modified by Ramon Engle

CREDITS (cut & pasted from YouTube):

Director: Damian Kulash, Jr.

Co-Director & Creative Director: Mary Fagot

Executive Producer: Fung Ni

Director of Photography: Luke Geissbuhler

Art Director: Julius Mak

Production Manager: Bihong,Chan

Assistant Director: Joan Chen

Photograph group:

Steadicam Operator: Alec Jarnagin

1st Assistant : Kenan Qi

Assistants: Xinfeng Zhang Hongyan, zhang Yanru, wang

Equipement: Wei Pang

Digital Image Engineer: Tiger

Equipement Company: Yiying Shanghai

Light Group:

Lightman: Kok Kin Wing

1st Assistant: Jingdong Wang

Light Assistant: Bin Xu Xinbin Jiang Yongchao Hu Chaoliang Wang Yang An

Light Equipment : Chenjun Zhou

Art Group:

1st Assistant: Ong Wan Hoong

Art Assistants: Harris Eddie Sequerah, Rae Chen

Props: Songyi Wu

Studio Factory Manager: Yubin Xia

Recordist: Yan Xia

PRODUCTION GROUP:

Executive Producer: Xiaoming Tang

Production Assistants: Jojo Ying Yuanbiao Wang Yong Dong Longhui Li Yi Zheng

Translator: Lingyi Chen, Yifei Gu

Runner: Chao Huang

Transport: Shuguang You

Casting: Fei Huang, Jingyuan Yuan

Choreography: Guanglei Zhang

Dancers: Weijia zhou, Chuanjing XU, Kaijie Wang, Xi Xu, Zhijing Cao, Yimian Song, Xuqin Hua, Wentao Fan, Qin Zhang, Xubin Geng, Chunmeng Yan

Costume:

Stylist Director: Mengjia Zhan

Stylists: Yuanjun Xiao, Shiqi Zhang, Yinghui Huang, Zhihui Wang, Chen Wang, Bin Lang, Huiting Wang

POST PRODUCTION GROUP:

Offline Editor: Fenny

TC : Jian Wang

Online user: CiCi & Yuqian Jin

Post Producer: Jojo Ying

Behind the Scene: Steven

Post Production Company: Liveplus Shanghai, Film Vally Shanghai

Music Studio : Take One, Shanghai

General Planner: Red Star Macalline “Two Days coming” program

Agency: 25hours, Shanghai

Production House: STEAM ,Shanghai

Advertising Agency Executive Creative Director: Lei Tao

Advertising Agency Creative Director: Song Zhang

Advertising Agency Art Director: Lei Shi, Binyan Huang

Account Director: Lingning Yan

Account Executive: Yan Huang, Da Li